Taken from Challenge Magazine:

“Reform is China’s second revolution”

Deng Xiaoping

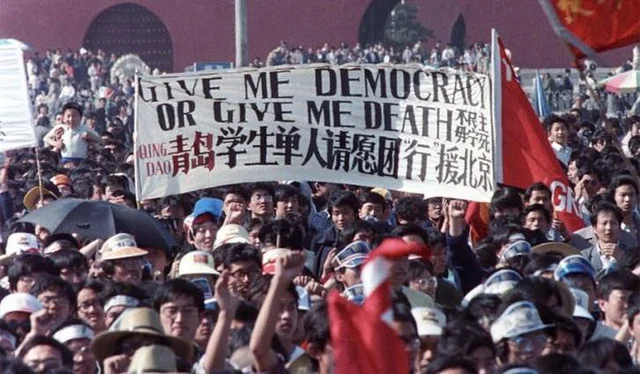

There are moments of history which serve as key ideological battlegrounds in the fight for socialism, and in the history of China, there are few events which cause as much contention, confusion, or emotion as the ones surrounding the Tiananmen Square student protests of 1989.

To those who oppose the rule of the Communist Party of China, the government crackdown represented a brutal act of authoritarian violence; a crushed uprising against a regime that had lost the support of the masses.

To the CPC’s defenders, these riots were anti-government and anti-socialist, or even a colour revolution which, if left unchecked, could have quickly led to a Soviet-style collapse.

Whatever your position today, we are living through a time of sharpened contradictions between China and the West, and these historical moments will continue to be raised again and again on the propaganda front of the ‘New Cold War’.

Misinformation abounds, so it is crucial that we study these moments of history both critically and fairly in order to expose the lies of those same, powerful forces who would rather manufacture consent for war than attempt any kind of cooperation.

First, in order to identify either the progressive or reactionary nature of an uprising, it is necessary to dig beneath the propaganda and surface elements to uncover the class interests at play.

Who composed the protests? What was their material basis and historical context? Were the protesters trying to build socialism, or tear it down? Contrary to those who believe that the events at Tiananmen Square have been cast down an Orwellian-style memory hole, the CPC actually dedicated ten full pages to answering these questions in an official Party history released for their 100th anniversary in 2021.

It is lazy to trust any single account without further analysis, but the government line is a good starting point, so I’ve included their interpretation below:

“In late 1988 and early 1989, while efforts to improve the economic environment and ensure economic order were ongoing, a small number of people in several major cities, but particularly Beijing, incited opposition to the leadership of the CPC and the socialist system, taking advantage of mistakes in the work of the Party and the government and people’s anxiety over inflation and resentment over the corruption of certain Party members and officials. […] The upheaval in Beijing eventually escalated into a counter-revolutionary rebellion.”

Here, we can see that the Party condemns the protests in the strongest possible terms, but especially the small group of instigators who they claim exploited Party mistakes, as well as legitimate concerns among the masses about corruption and the state of the economy.

In the same text, they mention that a combination of factors led to the protests, both international and domestic. Internationally, Tiananmen was part of the wave of discontent in the late 80s which spread across socialist states all over the world, exacerbated by Cold War aggression from the capitalist West and culminating in the collapse of the USSR and the socialist bloc. Domestically, China was going through its own turbulent transition at the end of the Mao years known as “reform and opening up”, which introduced many new contradictions into Chinese society.

Similar to Lenin’s National Economic Plan, it was argued that Deng Xiaoping’s economic and political changes were necessary in order to save socialism and China itself. However, if not handled carefully, the new contradictions threatened to overwhelm and collapse the entire system.

What were the issues with “reform”?

As Deng began integrating freer markets into the economy in order to boost production and reduce inefficiency, price controls were no longer set by the state. This sudden change led to soaring inflation, panic buying, and corruption among Party officials and their families who exploited their positions to buy goods at state prices and then sell for a profit on the market, breeding resentment among the masses.

Chen Yun, a highly influential proletarian economist and leading party official who had helped Deng design his reforms, was a strong advocate of “bird cage economics” (where the cage represented state control, the size of which could be altered; and where the bird represented the market which, for now at least, was a necessary fixture).

Chen was an outspoken critic in the Mao years of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, but also criticised Deng for “increasing the size of the cage” too much, too fast. The government later admitted to some mistakes, and Chen’s criticisms went on to inspire the stronger state intervention over the market shown by Deng’s successors, including Xi Jinping.

What were the issues with “opening up”?

The government recognised that to become strong, China could no longer isolate itself from the global market, and that it would need to survive alongside capitalist nations like the US. This meant greater exposure to Western culture at a time when US capitalism and liberal democracy were at peak ideological influence.

“Opening up” had a profound effect on the new generation of students who felt stifled by economic hardship and their duty to their country and socialism. Many students instead fantasised about a Western liberal and consumerist alternative which they had access to for the first time.

Wu’erkaixi, one of the main student protest leaders, put it this way:

“[T]here’s never been a generation that’s seen that the outside world is so beautiful… Does our generation have anything? We don’t have the goals our parents had. We don’t have the fanatical idealism our older brothers and sisters once had. So, what do we want? …Nike shoes, lots of free time to take our girlfriend to a bar, the freedom to discuss an issue with someone and to get a little respect from society.”

Wu’erkaixi

Despite their glorified image in the West, most of the students were young and idealistic. Their demands varied from grand, but uncertain visions of “democracy” to petty liberties like the freedom to date on campus, and they could not unify around a solution to their problems.

This disunity led to several splits in the movement and ebbs and flows in the numbers on the square. One notable split was between the more radical hunger strikers and the students who ended their class boycott once the government had given them some recognition.

Indeed, some found it shocking how quickly the more radical elements abandoned their democratic ideals to seize control of the movement. That said, the disunity among the protesters was also mirrored by disunity in the Party leadership, and a failure to quickly determine whether the protests were progressive or reactionary led to mixed messaging from Party outlets and a failure to resolve the protests quickly, something which could have saved lives later on.

This confusion stemmed from the fact that many of the students did in fact consider themselves socialists and genuinely wanted to save China and improve the lives of themselves and their fellow countrymen. Others, like student leader Chai Ling, hid the fact that what they actually wanted was violence and regime change:

“How can we tell them that what we’re actually hoping for is bloodshed? For the moment when the government has no choice but to brazenly butcher the people? Only when the square is awash with blood will the people of China open their eyes. Only then will they really be united.”

Chai Ling

Some protesters, either consciously or unconsciously, believed that the answer to China’s woes was capitalism. For those who held this belief unconsciously, there existed a culture of idolising the West, or at least anti-socialist reactionaries like Gorbachev, who was jealously perceived by many students at the time as a radical progressive.

Those who were more explicit in their support for capitalism were influenced by intellectuals like Wang Ruowang and especially Fang Lizhi who toured universities at the time to spread the idea that China’s poverty and underdevelopment were a result of socialism. This was one of the factors leading to the earlier 1986 student protests in Hefei, Shanghai, and Nanjing, and Hu Yaobang, a party official who was seen to sympathise with these protests, was therefore condemned by Deng for “bourgeois liberalisation”.

Hu had a large student following, and the fact that his death sparked the first protests at Tiananmen in 1989 was another hint (at least in part) to its liberal roots. After the protests, Fang Lizhi was correctly accused by the government of attempting to instigate a regime change, but was shepherded out of the country by the CIA.

Discontent about the failure to tackle economic problems manifested among students in reactionary ways, like the scapegoating of minority groups. As part of China’s strong diplomatic ties with Africa, rooted in Mao and Zhou Enlai’s advocacy of third world solidarity, many African students were given financial support to study abroad at Chinese universities, and even had better accommodation than the locals.

Some students believed that, since all Africans must be poor, they could only be at a Chinese university through handouts, rather than merit. Racist jealousy over this, as well as other things like interracial dating, led to a riot at Nanjing University in 1988. Several thousand Chinese students were involved in the verbal and physical attacks against African students at the time, and some of these protesters would later be at Tiananmen as well with banners reading “Stop Taking Advantage of Chinese Women”.

Deng Xiaoping always maintained that the Tiananmen Square protests would have happened “sooner or later” due to government mistakes and internal contradictions in the country, but the results of these errors were severe.

The chaos which ensued after martial law was declared led to tragic losses on both sides, with the most likely estimates putting the death toll at over 300 in total. The vast majority, if not all of these deaths occurred in outbreaks of violence around Beijing both before and after the square was cleared.

Some protesters had managed to acquire guns, and there was a shoot-out to the west of the square which soldiers claim was due to snipers targeting them from wealthy, high-rise apartment blocks in the area. Footage was also released of protesters throwing Molotov cocktails at army vehicles, lynching soldiers, incinerating them, hanging their bodies from overpasses, and even disembowelling them.

These graphic images were later shown at schools and universities to convince students that the crackdown was warranted because of those protesters who had been willing to use violence against the government. This went some way towards repairing what many felt was broken trust between the people and the state at the time.

Although the contradictions which led to the protests seemed to originate in China itself, rather than being seeded by the West to incite a “colour revolution”, it is undeniable that capitalist countries worked to exacerbate the crisis at Tiananmen as much as they could, both during the protests and after.

For example, Western propaganda outlets like Voice of America, which is owned by the US state, were a common feature in Chinese homes at the time and gave ample coverage of the protests, supporting the calls for “democracy” and encouraging rebellion. Western propaganda also worked to distort the narrative in later reports, including inflating the death tally to “thousands” rather than hundreds, or arguing that there had been a “massacre” on the square, despite protesters and Western journalists on the scene, as well as leaked cables from the US embassy testifying against this.

Camera footage of “Tank Man”, a figurehead for Western protest supporters who temporarily blocked a line of tanks as they were leaving the square for other parts of Beijing, was also misrepresented to imply his arrest or “disappearance” by the government, or even that he was crushed by the tanks. In reality, other protesters are filmed hurrying him away, and it is most likely that Tank Man was never identified, as the government claims.

Unsurprisingly, there was also CIA involvement in the uprising. While Hong Kong was still under British colonial rule, the CIA and MI5 used the territory as a launch pad to help over 400 protest leaders and anti-socialist intellectuals and activists flee the country through “Operation Yellowbird”, with help from Hong Kong gangsters, the Triads. A lot of this operation was performed through an organisation called the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, set up by wealthy Hong Kong celebrities and activists.

This organisation’s stated goals included overthrowing the Chinese government, and they drew up a list of 40 dissidents involved in the protests to form a “democratic Chinese government in exile” (the same strategy used against Tibet). Many of those who were helped to escape prosecution were given Ivy League admissions and scholarships, and some protest leaders like Chai Ling already had US visas while the protests were ongoing, suggesting that they had always planned to flee to the West and abandon their compatriots to their fates. Operation Yellowbird finally ended in 1997 when Hong Kong was returned to China.

Despite the traumatic nature of the Tiananmen Square uprising, our ruling classes continue to disturb its memory for personal gain, with the 4th June serving as their annual reminder that despite raging poverty, unemployment, homelessness, and the rest, we are lucky because we live under so-called democracies, to which there is no alternative.

To them, and to those sham socialists who hope that another revolution will bring a higher, “truer” stage of socialism to China, that day still holds an almost mythological status as the closest the People’s Republic ever came to being overthrown, although it seems that only the liberals can articulate what would come in its place.

There are many lessons to be learned from Tiananmen Square.

From the Party, we learn the importance of correct dialectical materialist analysis, quick decision-making, and unity under pressure. From the protests, we learn the dangers of propaganda, soft power, an unstable economy, corruption, and of neglecting political education among the youth.

And from those students who genuinely desired a more robust socialist democracy, if perhaps too soon, we learn that in a world still dominated by imperialist powers and class conflict, too much democracy, ironically, can pose a danger to itself. Indeed, the dissolution of the Soviet Union just two years after the protests served as a wake-up call to many of those students about just how fragile their political system really was.

Thankfully, the People’s Republic continued to carry socialism with Chinese characteristics into the 21st Century, and China’s achievements in poverty alleviation, COVID response, anti-corruption, employment, housing, environmental leadership, and yes, democracy, continue to serve as a model for oppressed people all over the world.

As China develops, government popularity soars and young people are gaining a renewed interest in Marxism. For all these reasons, a repeat of Tiananmen Square looks increasingly unlikely, although we should be wary of continued destabilisation attempts from the West in areas like Taiwan and Xinjiang. After all, so long as China continues to carve a path towards the highest form of democracy, communism, it is the duty of young people to defend it.

Eben Dombay Williams, is a member of the YCL’s Glasgow branch

Source: Challenge Magazine