Taken from Challenge Magazine:

When I sat down to begin this look at the current debates on the left about taking measures to be partly or as near as totally anonymous, I realised that from the off I would be taking a side: I would already be throwing my hat in with the pro-anonymity camp because I’d be writing under a pen name.

I am a committed revolutionary communist, and I am lucky enough to have a day job that is directly part of the class struggle and advances the basic goal of communists in a period of rebuilding and regrowth: building working-class power. Although some of my colleagues and members know I’m a communist because I have told them, when going into negotiations it makes no sense for the other side of the table — employers etc. to know that I am a communist.

Even if they don’t use this information to denounce me to my members — “he’s just using you to advance a political agenda” or “this person defends dictatorships” — it may at the very least convince them, correctly, that I am negotiating in bad faith: no, I don’t actually care about the good of their business or the market, yes, I do want to nationalise their industry and seize their property.

Of course, I am hardly alone on the left in using a pen name; Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov had no less than 146 fake names, including his most famous, Lenin. And the practice continues to the present day, in places far from the dangers of revolutionary Russia a century ago. It’s commonplace in any left-wing paper, magazine or message board; indeed, how many of us are not using a pseudonym on social media already?

But beyond pen names, are there steps we should take to conceal our identities, and more importantly, should we? How do we balance keeping ourselves safe with being identifiable to people who want to work with us or join us? To summarise the debate going on within our movement I spoke to four people — keeping with the spirit of the piece, their names have been changed.

“Total anonymity is impossible but partial anonymity is essential” –– George, tech worker, London CPB

I think people who have argued there is no point in trying to stay completely anonymous as members of formal communist organisations are probably right, in the grand scheme of things: the kind of promises of encrypted messaging apps, even if we take them at their word, only last as long as any piece of tech remains in your hands, and if you have any messenger app open when you lose possession of a device, not just you, but your network is exposed. If the police seize any of your tech, I would err on the side of assuming that they have absolutely everything you have ever put on that piece of tech, depending on how interested in you they are.

If you want a personal social media presence, or a political one that people can contact to get involved or whatever, similarly, you can just assume that in the worst circumstances any information from that is available to the police. If communist parties and groups were banned tomorrow like Islamist and Nazi groups have been, all our information would be handed over by Facebook, Twitter etc. to the police and security services. We hope the outcry from this kind of political repression would be too severe for the state to be able to do something like this, and at the stage we are at now, it seems so unlikely, that the benefits from having social media as an organising and propaganda tool far outweigh not having it.

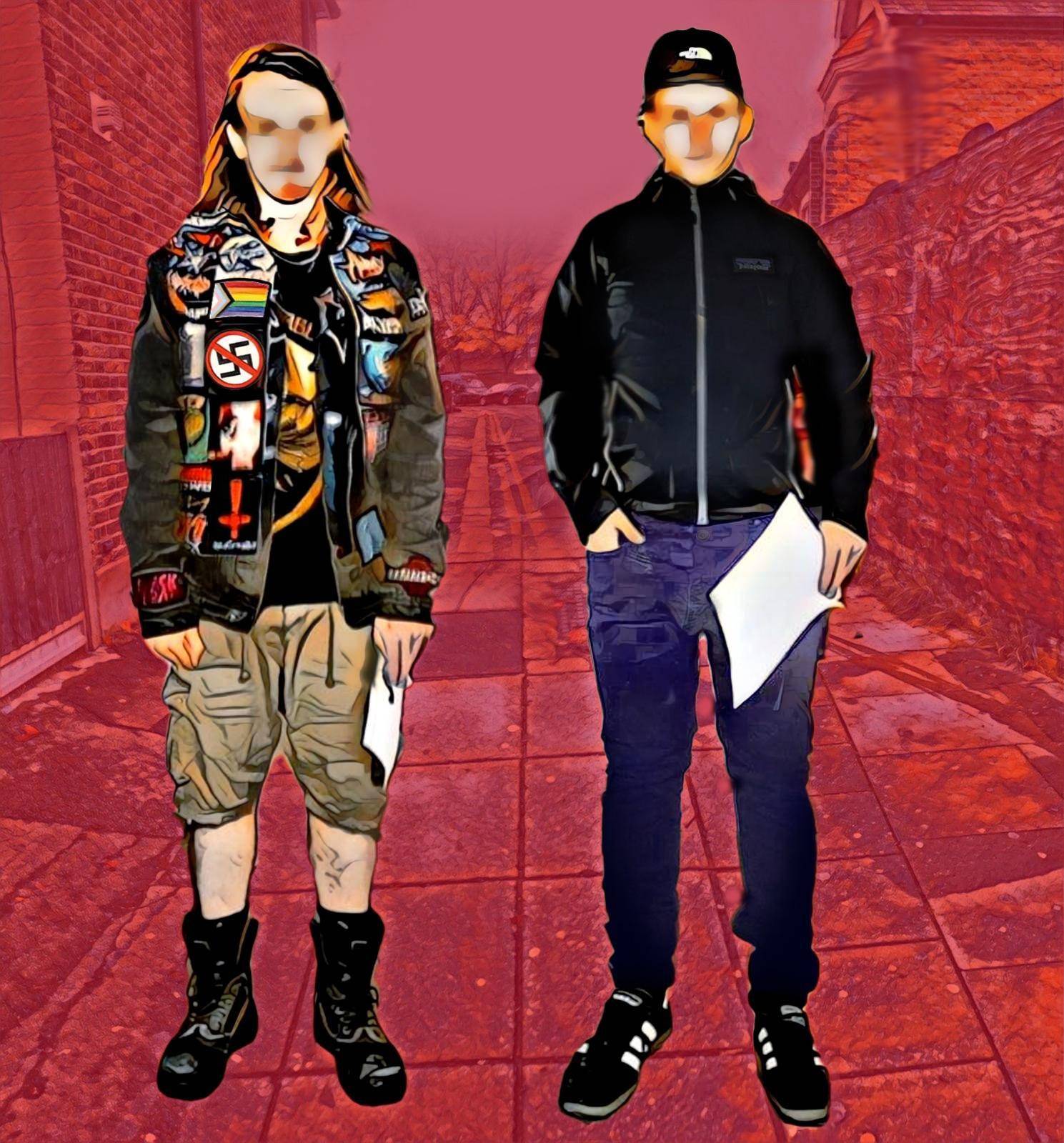

However, this doesn’t mean we should embrace having all our information out there. Day to day, I completely agree that pictures should not be posted showing the faces of communist activists without a good reason, such as they are leading members and public figures. Because the right wing is already compiling lists of us; I am not going to name the sites that do it, but they have scraped social media and cross-referenced it with names on things like trade union documents, online lefty news articles etc. and built public databases of communists and socialists that employers, and of course, people that just hate communists and want to do us harm in some way, can access. This is a huge wake-up call. Every step you can take as a group or individual, like having your personal profiles set to private, without pics of you, and with a fake name, and blurring faces in pictures of communist activity posted online, would effectively stop this doxxing of activists. Doxxers might get some info, like that you are in a union or campaign, but not what you look like, or that you’re a communist. Honestly, I don’t really see the downside: you meet someone for the first time and they say ‘hello Simon’ and you say ‘actually my name is Stewart that’s just my Facebook name’ and they say ‘ok.’

“Having a loose dress code kept us safe and went down well with the public” — Martin, Cop26 demo organiser, Glasgow YCL

Going into organising the red block on the main Cop26 demo in November 2021 it was decided that we’d wear similar clothes, hats and caps, and red face warmers. We did this partly to identify ourselves which worked well as we were easily the largest organisational block on the march, and to keep ourselves safe from being identified by the inevitable media attention. The idea for the dress code came from some of our members who are football fans who get targeted for their politics and by the police.

On the day of the big demo, our block was targeted by the police too, and suffered some arrests and far more attempted arrests (which we were able to resist) because the police arbitrarily decided to try and stop us from moving. I am absolutely certain that if we had been more easily identifiable there would have been more arrests after the day. Given it was hard to tell one person from another, it was just that much more effort for the police. Obviously, what I’ve just said will set off alarm bells for some people who worry about the left going down the rabbit hole of pointless stand-offs with the police, but honestly, the kind of treatment we received is absolutely inevitable if the left is effective and the police will do the same to you if you are a picket, on a demo in the community, resisting an eviction, whatever. We already know they are opposed to us for political reasons, so precautions make sense.

The police operation against our Cop26 block completely backfired for them: we received support from all others on the march, from leading trade unionists and even officially from trade union and other campaign bodies. We got prime billing in the news and applications to join flew in. No one said “I’d support them but I don’t like the way they are dressed” other than a couple of far-left political rivals who oppose us anyway. Lots of normal people – the aforementioned football fans for example – gave us credit for taking things seriously. Since then, we have used similar dress codes at other national events and also locally when there has only been a handful of us, and the people who would supposedly be alienated by it – union members on picket lines – have been really positive. Before we started doing it we were warned that carrying red flags and wearing face warmers would “not be allowed” and “go down badly” — I think we have comprehensively proven that’s not the case.

I’d like to echo the point about jobs. On the Monday after the demo, I was in work – I work on the shop floor of a multinational corporation that is deeply opposed to unions. The footage of the red block was playing on the news on the TV in the canteen and people had stopped to watch it. Someone shouted, “Hey that’s Martin!” And my blood ran cold. It turned out it was a joke because they know I’m a bit of a lefty. The funny thing was, I was actually on the screen: they just didn’t recognise me.

“We shouldn’t be putting members’ safety in jeopardy due to different opinions on aesthetics” — Lucy, education worker, London YCL

Working in a school, I would be more likely to do openly communist activity knowing I have the option to mask up or have my face blurred. If not, I wouldn’t attend larger demos and would be hesitant to have anything put on social media. I think it’s very necessary as a safeguarding measure. This is essential to comrades for various reasons – work safety being only one of them. I honestly think it should be mandatory for this reason alone and we shouldn’t be putting members’ safety in jeopardy due to different opinions on aesthetics. I honestly have no concerns about people not wanting to speak to the YCL because of how we appear — I understand that membership has been increasing and haven’t seen a correlation between the dress code at demos and people not wanting to sign up.

I’ve never heard that the dress code “intimidates women” from women members or from others — but of course, I wouldn’t be dismissive if this was a take. If it is an issue, I personally think the fact that men are overrepresented might be the overriding reason for that, rather than what the men are wearing.

“All of these things are part of communist work in the British tradition” — Frank, Manchester CPB

When this whole debate began, I really appreciated the chance to drop aspects of my personal identity to adopt a common identity, beyond security concerns, because it’s made me feel more confident about our political work and being taken seriously. When I look at pictures of left-wing groups post online now I just wonder why they don’t see how counterproductive it is to be so identifiable, not just as individuals but as types of individuals: it makes much more sense to make the simple statement that ten communists attended some event rather than identifying and pigeon-holing each of those ten people.

I’ve been responsible for following the emerging anonymity steps in my region and I have to say it goes a lot deeper than simply what we are wearing and what message that sends out. There is the security aspect that I think others have covered, but there is also a question of seriousness about politics. I’ve been lots of different things growing up, a metaller, a punk, and left-wing organisations I joined never said anything about these weird and wacky identities, and I really wish they had. Or rather, I am not surprised they didn’t because they are not serious groups – they are support networks for people who feel different, at odds with the world, out of touch – and like to wear that on their sleeve. I don’t have a problem with that per se, just like I don’t regret having a laugh in subcultural music scenes growing up, but if you want to go out and organise normal people you don’t want to be wearing a sign that says “I have a gripe with the normal world.”

The only way we are going to gain any edge over the ruling class is if we are willing to sacrifice more for our cause than the people are willing to sacrifice to gain or maintain a position in capitalism. It makes no sense then, when supposed revolutionaries have this back to front, and are happy to change their identities for work, but refuse to do so for political struggle. At the end of the day, this is a movement which needs us to be ready to give it everything — we might need to move city, change our names, work abroad — all of these things are part of communist work in the British tradition, I’m not even thinking of if things became as serious as they are elsewhere. When I speak to comrades now to give them a steer about any of this, I see resistance to it as being incompatible with communist work.

Conclusion: anonymity as the basic assumption

This debate and these opinions didn’t fall from the sky: they are the result of a new generation of working-class militants joining the Marxist left, and transitioning from a liberal-reformist approach to politics to a revolutionary one. To restate the central pillar of my argument: I don’t want my legal name and “member of the Communist Party” next to it, if it can be avoided, not because I am not committed to the politics of the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism, nationalisation of major industries with no compensation, seizure of property from the rich and the dictatorship of the proletarian party — but because I am absolutely committed to this, and expect to take serious steps towards achieving it in my lifetime. For that reason, I expect to face opposition from the capitalists and their state and the political enemies of the left, and see no reason to give them unnecessary advance warning.

The desire to loudly and proudly declare: “I am a Communist” is a trend I have observed within our own movement. Young comrades are excited to join a growing organisation of militant young workers and students and argue we should wear our politics on our sleeves, perhaps trying to normalise communist views in the process. Obviously, there are situations where being direct and open about your politics and your programme is the best course of action, but that is not the case in all situations. In the digital age, you have no control over who has access to this information, once a single photo of you is taken, an article is published in your name, or even you are tagged by a comrade online. We have walked blindly from the newspaper age, where you might appear in the press if you were very famous or very unlucky, in print on one day, to a world where you can do a stall in a quiet street and pictures of it will mark you and your politics out for life.

This doesn’t mean that we avoid having almost any public face, but that we are more selective than we currently are about when and how to have one — measures that were common sense in the past need to be updated for an age when everyone is carrying a digital camera linked to the internet. Digital and social media create networks of information about you, complete with names, photos, and connections, which can be accessed by anyone. My advice to comrades is simple; focus on your political work, not your political brand, limit your contributions to these networks, and remain in relative anonymity. Total anonymity might be impossible, but taking steps to protect your identity is simply common sense. If we go forward with the assumption of relative anonymity as a basic, we give comrades the choice to change that if and when we think they should or need to — honing and refining our message, and our messengers, in the process.

Jesse Cook

Source: Challenge Magazine