The following is adapted from a talk given at the Marxist School in New York City in 2022.

As we see the erosion of the rights that working people have won by a Supreme Court that wants to roll people’s rights back to 1787 and that cavalierly disregards the will of the majority, it is a good time to put ruling-class strategies in the spotlight. In this article I will describe briefly what we mean by the ruling class, arguing that the class as a whole is a social actor more than a characteristic that adheres to individuals one at a time. Next, the nature of the democratic struggle in the current day is addressed. Finally, I will outline seven strategies that the ruling class has used over time and in contemporary politics to curtail the voice of the workers in government and damage the opportunities to make policies that serve actual human needs.

A caveat: this article barely scratches the surface in its examination of the ruling-class agenda. I hope here to just offer a starting point and an approach that notices patterns over time so we can better plan the fight-back.

What is the ruling class and who comprises it?

A ruling class is a collective social actor. It consists of those who control the means by which a society produces and distributes its goods and services, and who in turn control the rest of the population though coercion, violence, exploitation, and cultural domination. In feudal societies, the ruling class consists of those who control productive land and who extract the value of people’s labor in the form of rents and tributes. In industrial societies, the ruling class consists of banks and other financial institutions, industrial corporations, large agribusiness, and distribution networks like Amazon. The ruling class has used its wealth and military might to nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, and establish connections everywhere (paraphrasing Marx and Engels), exploiting the people they encounter around the world and stealing their resources.

The Program of the CPUSA characterizes the ruling class in the United States as “one of the most controlling, entrenched capitalist ruling classes ever, concentrating enormous political, economic, and military power in the hands of a few transnational corporations, led by global finance banks and the politicians who do their bidding.”

While the ruling class has common interests and a social agenda, it is not always unified, and some segments are more dangerous than others. As Georgi Dimitrov pointed out in 1936, fascism is defined as the rule by “the most reactionary, most chauvinistic and most imperialist elements of finance capital.” It is segmented, and it also attempts to divide the working class to more effectively exploit it. For this purpose, the ruling class uses racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia.

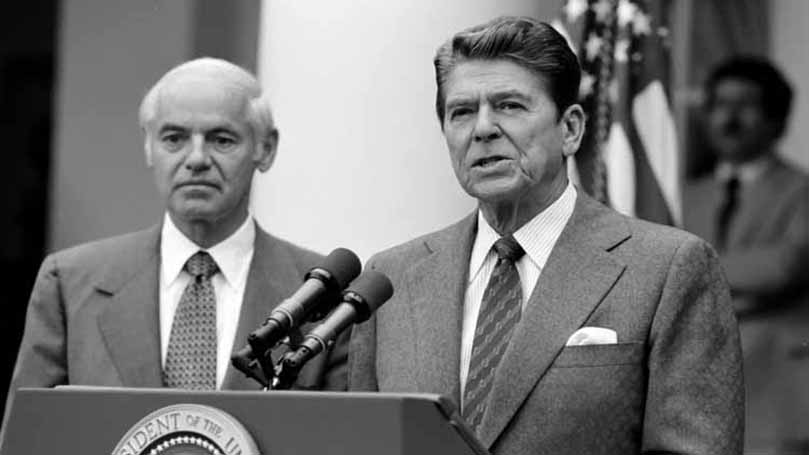

The global ruling class and its U.S. counterpart suffered some setbacks in the 1960s and ’70s but came roaring back in the 1980s during the administration of the union-busting, “small government” president, Ronald Reagan. Taking the lead from their president, corporations continued a process of gutting labor rights, eventually whittling union membership down to 10% from a high of 35% in 1954. The newly invigorated ruling class used government power to bust unions, and at every chance undermined the role of government to make workers’ lives better. Ruling-class interests invested in right-wing think tanks and eventually endowed conservative institutes at major universities. They brought in religious fundamentalists, who fomented a moral panic over abortion that deflected attention from the profits the ruling class was amassing.

We need to be sure to think about the ruling class as an agent of social change. In our party, we analyze society from a structural point of view, instead of looking at individual members of the class. In bourgeois social science, “class” is sometimes conceived as an individual-level characteristic and used to explain individual-level behaviors and attitudes. But the dynamics of social change as understood and explained by Marxist-Leninist analysis are such that we aren’t concerned with whether one person or another “is” working class or ruling class, but how their actions contribute to the movement of the working class or to the repression and exploitation of the working class. We focus on the broader class struggle in society.

What is the democratic struggle?

Democracy, from the Greek words for “government or authority of the people,” is a form of government in which the voice of the people shapes the affairs of government, all citizens have equal rights before the law, and the will of the majority prevails. Democracy is seen as a social, political, and economic system. But we recognize that economic relations change first, and political forms change in response. As Lenin argued, “any democracy as a form of political organization of society, ultimately serves production and is ultimately determined by the production relations of the given society.”

Our goal as Communists is to unite the working class, to increase its autonomy and independence. A revolutionary majority is our goal, one based on mass organizations and political parties, that will “make it politically impossible for the ruling class to use political or military means to return to power.” We are working toward the establishment of a socialist democracy, described as one in which “citizens’ rights are not just proclaimed, but are consolidated by law and secured by the fact that exploitation by private employers is ended and the crises of capitalism have passed” (Road to Socialism).

Our country’s revolutionary history is characterized by massive struggles to protect and expand democracy, from adding the Bill of Rights to the Constitution, to the referendum in the past few years to restore voting rights to felons in Florida.

It stands to reason, if the working class is the vast majority of people, how could it be defeated? In a country that purports to be not just a democracy, but the “most democratic country on earth,” how is the voice of the working class silenced and its power undercut? The ruling class has its methods, and that’s what we’re going to talk about here. I want to focus on some of the specific ways that the ruling class has shaped the United States as a state, as a nation, and as an imperialist power, both historically and in the current day. Specifically, how has it worked against the struggle for greater power for the working class? How has it managed to put into place the maneuverings and manipulations that divide us? The ruling class is in a constant struggle to contract the electorate, curtail civil liberties, and give the rich every opportunity to dominate elections. Democratic rights in capitalist society are under constant attack.

It stands to reason, if the working class is the vast majority of people, how could it be defeated? In a country that purports to be not just a democracy, but the “most democratic country on earth,” how is the voice of the working class silenced and its power undercut? The ruling class has its methods, and that’s what we’re going to talk about here. I want to focus on some of the specific ways that the ruling class has shaped the United States as a state, as a nation, and as an imperialist power, both historically and in the current day. Specifically, how has it worked against the struggle for greater power for the working class? How has it managed to put into place the maneuverings and manipulations that divide us? The ruling class is in a constant struggle to contract the electorate, curtail civil liberties, and give the rich every opportunity to dominate elections. Democratic rights in capitalist society are under constant attack.

If democracy is said to mean people actually having power in government, how can we measure it? For bourgeois political science, simply having elections is interpreted as being a democracy. In graduate school I studied elections in Jamaica in the post-colonial period, during a time when the U.S. praised Jamaica for its “steadfast commitment to democratic traditions,” but it was clear to see that the will of the people was almost never expressed in those contests. Institutions that were set up by the ruling class and approved by the colonial powers chose the candidates and arranged for their victories, and for the most part carried on policies that served the imperialists and their local henchmen. Still, when the masses were mobilized and activated in the 1970s, and politicians felt compelled to listen, significant advancements were made in the conditions of the working classes (before those efforts were stymied by the decade’s end with the help of the CIA and U.S. Department of State).

Seven ruling-class strategies

1. Overturning elections

If democracy means majority rule, what does the ruling class do when elections are used to challenge the economic and social status quo? Thinking about this reminded me of Eddie Carthan, who in 1976 was the first Black person elected mayor of Tchula, Mississippi, since the days of Reconstruction. After his election, the white remnants of the local plantocracy stepped in immediately and were determined that Carthan would not be mayor. They locked him out of city hall, hounded him, brought him up on trumped-up charges, and sent him to prison.

Years later, in 2015, Carthan was again elected, this time as Holmes County supervisor. After four years of public service, the state auditor of Mississippi said his election was fraudulent because he filed a paper wrong, and he was to repay all his salary and benefits he received since he was elected to the position.

Carthan’s case involves local politics, but as we saw in January 2021, an outright overturning of the will of the majority of the voters is a threat even at the level of the highest elected office.

2. Limits on the franchise

For those who want to attack democratic rights, limiting the franchise is an obvious strategy, something that the ruling class has used to limit the power of the working class since the colonial origins of this country. In Boston in the early 1700s, wealth was consolidated in the top 1% of the population (which owned 44% of the wealth), and voting rights were limited to white men who owned property.

In the South, fear of a Black-white alliance led the Virginia Assembly to pass the “slave codes,” laws that involved discipline and punishment applicable only to the enslaved. The assembly also gave indentured servants specific advantages when their terms of indenture were over, including free land grants and provisions.

When the constitution was drawn up in 1776, it consolidated and institutionalized a set of power dynamics that included, in Howard Zinn’s words, “the inferior position of blacks, the exclusion of Indians . . . [and] the establishment of supremacy for the rich and powerful in the new nation.” Most of the men who wrote the constitution were “men of wealth, in land, slaves, manufacturing, or shipping.” They constructed a federal government structure that protected their specific interests: protective tariffs for the manufacturers, protection for land speculators against Indians, security against slave revolts for the plantation owners, etc. Women, the enslaved, and people without property were, of course, excluded from the process.

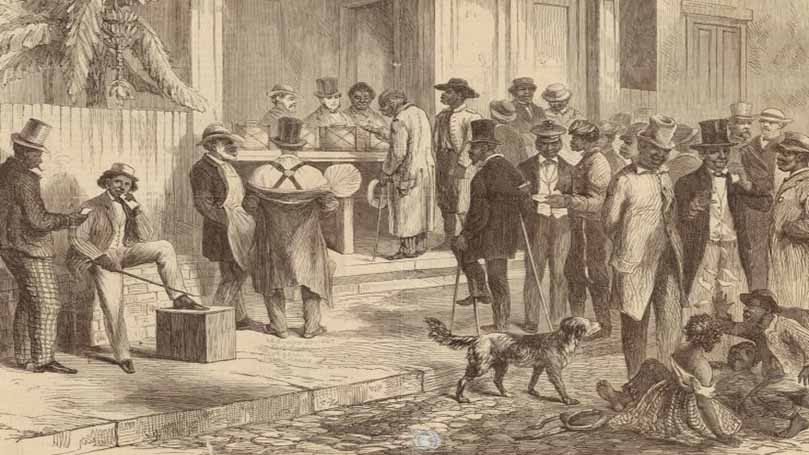

During the brief period after the Civil War when African Americans in the South voted, democracy flowered and policies addressing equity and inclusion flourished. The Thirteenth Amendment outlawed slavery, and the Fourteenth declared that all persons born or naturalized in the U.S. are citizens. The Fifteenth Amendment declared the “right of citizens of the U.S. to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the U.S. or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The first Civil Rights Act that outlawed the exclusion of African Americans from public accommodations was in 1866.

But soon after Lincoln’s death, President Andrew Johnson led the ruling class in rolling back the gains of Reconstruction. By 1940, only 3% of eligible African Americans in the South were registered to vote. Jim Crow laws like literacy tests, poll taxes, violence, and intimidation kept African Americans from voting (ACLU Timeline).

Those limits on the franchise had lasting effects. For example, why did labor parties develop across the industrial world, but never in the United States? Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward voice one widely accepted reason. “Partial disfranchisement of working people” in the early part of the twentieth century, while socialist parties were in development in Europe, “helps explain why no comparable labor-based political party here.”

Legislative attempts to limit the franchise are alive and well today. Despite Florida voters’ overwhelmingly supporting a referendum that allowed ex-felons the right to vote, the DeSantis administration and its sycophant legislature passed a rule that ex-felons could not vote until all fines and fees are paid. People leave Florida prisons owing thousands of dollars to the state. In one recent case, Kelvin Bolton, an ex-felon with a history of mental illness and cognitive challenges, who was persuaded to register to vote as he left prison, voted, then was charged with voter fraud and fined thousands of dollars more. Bolton is only one of many people singled out for prosecution. It’s a war on voting in the state of Florida, and elsewhere.

3. Violence and intimidation

The ruling class doesn’t usually do its own dirty work, but ruling-class minions are brought in to do their bidding, including both vigilante violence and state-sponsored police brutality. In the post–Civil War era, the ruling class of white economic elites organized the Ku Klux Klan and other terrorist groups, recounts Howard Zinn. Between 1882 and 1968, there were 4,743 lynchings in the U.S., that is, extrajudicial killings. Bloody Sunday, when police beat voting rights marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965, was a signal incident in the fight for voting rights.

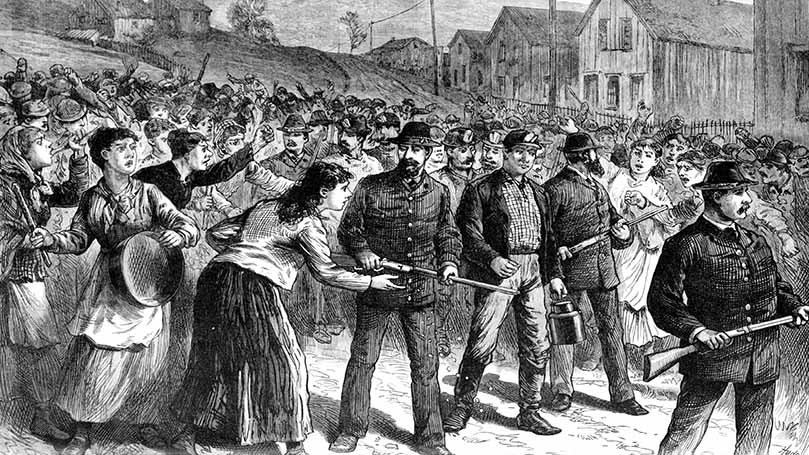

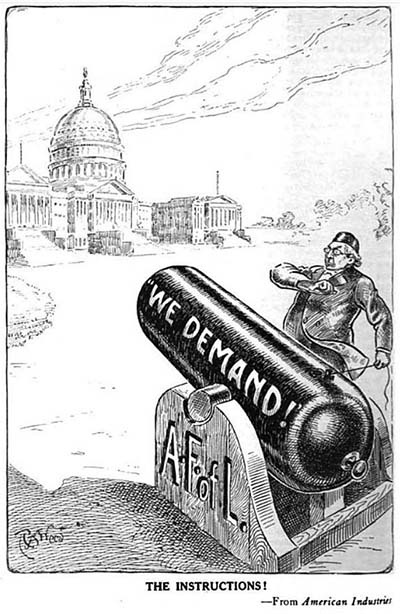

Mobs and police are not the only forces employed to break working-class power. In the late 19th century, corporations formed private armies to use force to break unions. Most famously, the Pinkerton Detective Agency had more men than the U.S. Army. Corporations wielded power without interference from the state. When murders were committed or injuries inflicted in busting unions, judges viewed unionization efforts as violations of the property rights of corporate owners, therefore corporate violence against workers was ruled defensive.

In the early part of the twentieth century, anti-union and “red scare” repression by government reached a fever pitch. As the authors of Labor’s Untold Story write, “The red scare was the heart of the open-shop drive of the National Association of Manufacturers,” whose president said in 1913 that the trade union movement was “an un-American, illegal and infamous conspiracy.” U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer put his Department of Justice at the service of the strike breakers, and on January 2, 1920, arrested 10,000 trade unionists across seven cities, many of whom suffered torture and humiliation at the hands of local law enforcement empowered by the U.S. Department of Justice. The Palmer Raids, as the evening came to be known, were widely condemned as lawless but effectively “frightened people and dampened militancy” (Boyer and Morais).

4. Representations and propaganda

In sociology’s version of critical race theory, specifically racial formation theory, structures are separated analytically from representations. Structures are laws, practices, and institutions that may either reinforce the racial hierarchy in society or undermine it. Structures have actual material consequences for people’s life chances. They may extend or shorten people’s lives or provide higher or lower wages. In contrast, representations are the ideas, myths, and meanings that attach to categories. While representations do not have direct material consequences, they still may either reinforce or undermine the hierarchy by mobilizing support for the structures that do make a difference to the distribution of resources. The ruling class uses symbols, narratives, myths, and images to limit the participation and power of the working class in government.

For example, during Reconstruction, when African Americans were being elected to legislatures and taking part in the political life of towns and states, Howard Zinn writes, a “great propaganda campaign was undertaken North and South” that claimed “that blacks were inept, lazy, corrupt, and ruinous to the governments of the South when they were in office.” The ruling class floated myths of a European “class” and brought poor white farmers “into the new alliance against blacks.”

The “ruling intellectual force,” as Marx and Engels called them, continued throughout the post-Reconstruction period to spread its ruling-class ideas, which are “nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships.” Some of these ideas were wedges invented to segment the working class into whites versus Blacks, men versus women, and old versus young. Other ideas, such as anti-union propaganda and “red scare” fear mongering, were aimed at the entire working class.

Representations are also important because they include myths of moral superiority and other justifications for their power that enable the ruling class to oppress the masses with impunity and an apparently clean conscience. In the realm of representation and symbolic politics, think about the question, are members of the ruling class “evil”? “Evil” is a metaphysical term. Certainly, lots of corporate power holders are completely heartless people (e.g., big pharma who raise the price of insulin, or the oil company that withholds data about the effect of fossil fuels), and they go about committing heinous acts against humanity seemingly without a care.

Representations are also important because they include myths of moral superiority and other justifications for their power that enable the ruling class to oppress the masses with impunity and an apparently clean conscience. In the realm of representation and symbolic politics, think about the question, are members of the ruling class “evil”? “Evil” is a metaphysical term. Certainly, lots of corporate power holders are completely heartless people (e.g., big pharma who raise the price of insulin, or the oil company that withholds data about the effect of fossil fuels), and they go about committing heinous acts against humanity seemingly without a care.

The point is, narratives and other representations of the industrial ruling class convince its members that they are entitled to their wealth: They worked hard, they have the best ideas, they paid their dues in their internships and residencies, their dads worked hard, they’ve made the best decisions, etc. A profound myth in American political culture is the Puritan concept that wealth is a sign of “blessing,” the opposite of “evil.” The wealthy see their wealth as an indication that one is among the saved and that God is hearing one’s prayers and bestowing His benevolence on one personally. The so-called prosperity gospel movement is one of the current iterations of this deeply rooted myth of the ruling class.

Of course, representations and propaganda are used by the ruling class to limit the franchise. We saw in 2016 especially how media are used to spread falsehoods that are aimed at contracting the electorate. A more insidious ruling-class idea that bourgeois political scientists tell people is that their vote doesn’t matter. This has the effect of contracting democracy and silencing the voice of the people. Between 35% and 60% of eligible voters don’t cast a ballot, and about 25% never vote. Many are simply convinced their vote doesn’t count, while others are daunted by the barriers to voting, which gets us to structures.

5. Structures

As described above, structures are laws, norms, bureaucratic practices, and institutions that have real material consequences. Some structural barriers that serve ruling-class interests masquerade as egalitarian but have outcomes that disproportionately affect the working class and its ability to use its franchise.

A study of nonvoters showed that factors included not being able to get off work in time or to physically access their polling place or failing to jump through the hoops of early registration or reregistration for “purged” voters. Bureaucratic structures that administer elections may make decisions that make voting more difficult in areas where working people live. This happened in Ohio in 2004, when the notorious Republican Secretary of State Kenneth Blackwell introduced all manner of limits. He rejected voter registration forms if they were on an incorrect stock of paper. He limited resources in cities and places where more people vote for the Democratic Party. Voters in the little college town of Oberlin, Ohio, waited eight or nine hours in line. The outcry from the masses of the electorate following the 2004 election led to the fairly generous early voting and mail voting options that the state has now.

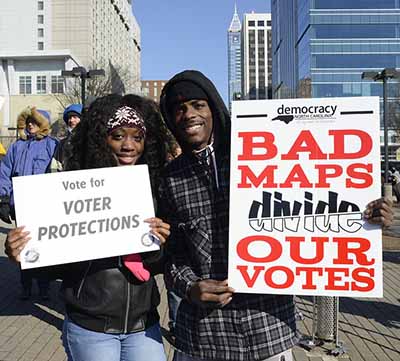

Another set of structures that have deleterious effects on the voice of the working class in government is redistricting. After the 2010 round of redistricting, maps were engineered so that a vast majority of the Ohio’s congressional delegation goes to the Republicans, though almost half of Ohio voters choose the Democratic party. Three-quarters of Ohio voters subsequently passed a law establishing a redistricting commission that was meant to remedy the extreme gerrymandering. But there were many loopholes in the law, and the GOP-dominated commission has passed three maps that the Ohio Supreme Court ruled as unconstitutional. The Republicans on the commission just waited it out, and now the 2022 midterms will proceed with an unconstitutional map.

Another set of structures that have deleterious effects on the voice of the working class in government is redistricting. After the 2010 round of redistricting, maps were engineered so that a vast majority of the Ohio’s congressional delegation goes to the Republicans, though almost half of Ohio voters choose the Democratic party. Three-quarters of Ohio voters subsequently passed a law establishing a redistricting commission that was meant to remedy the extreme gerrymandering. But there were many loopholes in the law, and the GOP-dominated commission has passed three maps that the Ohio Supreme Court ruled as unconstitutional. The Republicans on the commission just waited it out, and now the 2022 midterms will proceed with an unconstitutional map.

Ohio of course is just one of many GOP-dominated states where voter restrictions are proliferating. In Florida the governor outdid his own lock-step legislature and drew his own electoral map, eliminating two African American–dominated districts. Voters’ rights groups challenge the most egregious limits on voting in the courts. That’s why it’s important that when we vote, we pay attention to what judges are running, in states where judges are elected.

Besides rules and regulations governing voting, a broader trend is feeding voter apathy and disillusion. The 1970s saw the full embrace of neoliberalism, and with it the decline in union density, the decline in corporate tax obligations, and the deregulation of industry. These have resulted in a working class that is often working more than one job to make ends meet, and that may mean four or five jobs held per household, for wages that can buy far less in the marketplace than they used to. People are impoverished by the process of getting a higher education, and young people are delaying beginning families because of their student loan debt and the high cost of health care and day care. Innovation and creativity are stifled by having a young generation beholden to work for corporate America just to pay off loans and maintain their health insurance.

6. Judiciary

The indifference to the idea of majority rule that we talked about earlier was reaffirmed in the Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade. Most people in this country do not want to see Roe overturned. But their will has been thwarted by a court dominated by jurists who were nominated by a president who didn’t win a majority of the votes, and who were ratified by senators who also represent a minority of the electorate. Experts in law say that even if a law was passed by Congress and signed into law by the president establishing women’s bodily autonomy, the Supreme Court could overturn it on the same grounds that they are using to justify this decision. It’s one of the first times in Supreme Court history that a precedent has been overturned in a way that takes rights away.

The Supreme Court as it is currently comprised was stolen from the working people of the United States by the reactionary ruling-class forces that want an end to government regulation of industry. It is a uniquely undemocratic branch of government, and each member has extraordinary powers. Two-thirds of the court were nominated by presidents who had failed to win a majority of votes across the country. One of the proposed efforts to redress the imbalance is the Judiciary Act of 2021, which would add three seats. Others would go add 10 or more new members. The people’s movement needs to incorporate these demands going forward.

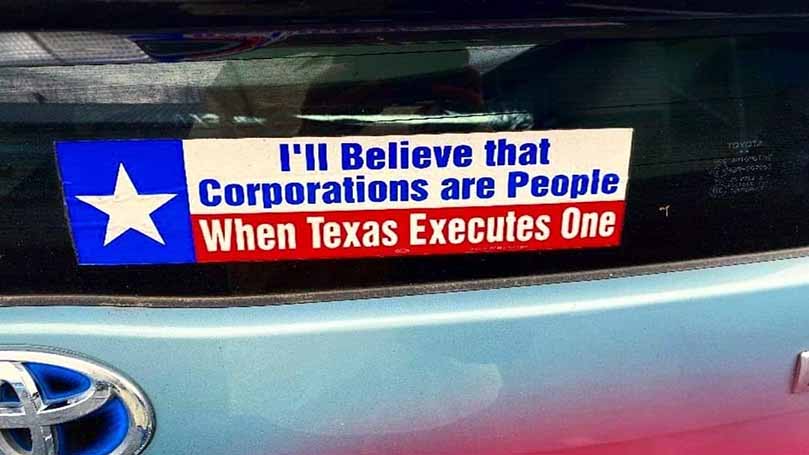

Also in the category of judicial restrictions on the voice of working people in government, through elections or otherwise, is the 2010 Citizens United v. FEC. This is the famous “corporations are people” case. Citizens United is a right-wing media company which produces right-wing media content. The company made a very negative and dubious “documentary” about Hillary Clinton, and the Federal Election Commission forbid it being aired too close to the primary election day. In its ruling, the Supreme Court overturned election restrictions that dated back more than a century. Corporations are now allowed to spend unlimited resources on election campaigns. It allowed for the establishment of super-PACs, political action committees that serve the wealthiest donors and that spend secret money through nonprofits that don’t disclose their donors.

As a result of the Citizens United ruling, the GOP in particular has benefited. A study in 2020 of election results by Abdul-Razzak, Prato, and Wolton found “strong evidence that these regulatory changes increase the electoral success of Republican candidates, thereby leading to more ideologically conservative legislatures.” They found the most evidence of pro-Republican effects of Citizens United where labor interests were weak and where corporate interest were closely aligned with the Republican Party.

In his minority opinion dissenting in the Citizens United case, Associate Justice John Paul Stevens declared that the court’s ruling represented “a rejection of the common sense of the American people, who have recognized a need to prevent corporations from undermining self government.”

7. Imperialism

“Despite the trappings of democracy, the U.S. government, like those of other imperialist countries, implements foreign policy as a direct instrument of monopoly capital, enabling the accumulation of capital for the monopolies” (Road to Socialism).

Of course, the ways that the U.S. ruling class reigns in the emerging power of the working class at home are numerous, two-faced, and often effective, and they are reinforced by an even more heavy-handed repression of democracy abroad. The U.S. undermines democratic outcomes in other countries by choosing to support certain candidates, by propaganda and misinformation, by violence and assassination. There’s abundant evidence of transnational corporate influence and CIA activity in the defeat of the Jamaican socialist prime minister, Michael Manley in 1980, and the installation of Reagan’s man Eddie Seaga. Recent reporting by the New York Times reveals the role of the banking industry in the centuries-long repression and impoverishment of the working class in Haiti. There are sadly innumerable examples.

Conclusion

The democratic struggle is a key one for the Communist Party and for the people’s movement more generally. While electing one over another candidate in a bourgeois democratic election may not bring on a miraculous socialist transformation, elections offer opportunities to build people’s coalitions to demand the voice of the majority in government, to enact policies that serve human needs and restore basic human rights. It is a truism that if voting in these elections didn’t matter, Republicans would not work so hard to take voting rights away. As we have seen in this review, they have an array of strategies that they have employed in the past and that we can continue to expect to see this year, in 2024, and beyond. We must organize to meet that challenge. There are several ways we can mobilize effectively: working with independent trade union and community-based political action organizations fighting for voting rights, for regulations that make it easier to vote, for fair district maps, and for greater numbers of registered voters.

Going beyond the election struggles of capitalist “democracy,” we need to keep our eyes on the prize of reversing the neoliberal slide downward, and attaining ever greater unity, autonomy, and political power of the working class. We need to struggle for labor rights, for livable wages, for bodily autonomy, and for rational climate policy.

Sources

Nour Abdul-Razzak, Carlo Prato, and Stephane Wolton, “After Citizens United: How Outside Spending Shapes American Democracy.” Electoral Studies 67, August 2020.

Richard Boyer and Herbert Morais, Labor’s Untold Story, 3rd ed. (UE, 1979).

CPUSA, The Road to Socialism Party Program, 2019.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology.

Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2015).

Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward, “Does Voting Matter?” in Power: A Critical Reader, edited by Daniel Egan and Levon A. Chorbajian, 68–78, 2005.

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York: Harper Perennial, 2015 [1980]).

Images: We the people, Move To Amend (Facebook); Reagan announcing he will fire PATCO air traffic controllers, White House, Wikipedia (public domain); Seattle teachers striker, Seattle Education Association (Facebook); Freedmen voting in New Orleans, 1867, Wikipedia (public domain); Pinkerton’s detectives escorting scabs during mining strike in Ohio, 1884, Wikipedia (public domain); Anti-union propaganda, Wikipedia (public domain); Gerrymandering protest, Stephen Melkisethian (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0); Anti-corporate-personhood bumpersticker, Move To Amend (Facebook).

Source: Communist Party U.S.A.